Advancing from Want to Worth

Do you ever find yourself tapping Buy Now at the end of a stressful day? In the moment, this small purchase may feel like a harmless act of self-care. But if you zoom out, you might see you’re moving away from self-care—and your financial goals—instead.

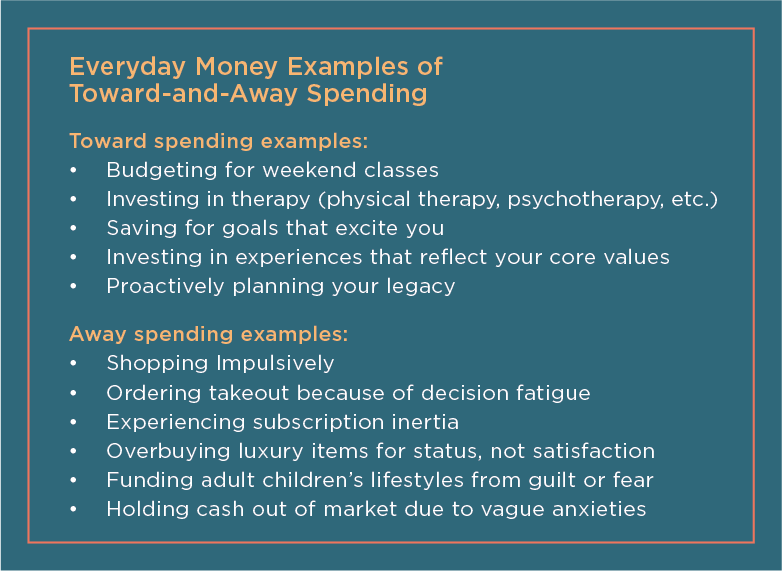

This sort of impulsive purchase can be described as an away move, something done to avoid discomfort. It distracts you from your stress, but it likely won’t help you meet your long-term goals.

We face a dozen similar decisions every day; moments when we can either act in a way that aligns with our goals and values or that simply helps us not feel worse. These aren’t always high-stakes decisions, but over time, the pattern matters.

When Good Intentions Meet Reality

A few years ago, my partner and I met with our CAPTRUST financial advisor, Veronica Karas, for a quarterly check-in. Karas gently pointed out that, despite having a healthy income and modest savings goals, we were consistently coming up short at the end of the month.

When we reviewed our spending, we noticed a theme: a steady stream of high-priced dinners. Some were celebrations, some were tied to business, and some were just fun nights out with family and friends.

At first, it felt like we had only a binary choice. We could give up entertaining, or we could give up saving. Eventually, we recognized there was a third path, one that didn’t require sacrifice, just more clarity. With a little self-reflection and a mindset shift, we would be able to recalibrate how we spent our money without giving up the things that brought us joy.

The Bigger Picture

Our spending patterns were no surprise to our advisor, who sees clients’ saving behaviors ebb and flow all the time. Karas suggests couples commit to regular financial wellness dates. “Review what made you feel fulfilled and what drained you,” she says. Ask yourself prompts like, “Which of my expenses felt aligned with my goals this month?” She also recommends regular advisor check-ins. “I always remind clients: Insight without rhythm will fade. Reflection is a practice, not a project.”

Karas says she sees common patterns in spending motivation among her clients, typically based on their phases of life. In their 30s, she says, clients tend to chase external validation and status items, like expensive cars or big homes. By their 60s, there’s a shift toward internal satisfaction—curating legacy, deepening relationships, or protecting time.

Rather than viewing financial planning as a trade-off between present happiness and future security, Karas encourages clients to seek a middle ground. “Form good habits that feel like wins right now and for the future, like simplifying, gifting, and planning meaningful experiences,” she says. “The key is recognizing that trade-ups beat trade-offs.”

Applying a New Framework

Melissa Kirsch, a writer for The New York Times, recommends a similar framework for moving toward a life you love. This means taking a broad look at your life—not just your spending. Her number one recommendation? Make two lists.

The first is a list of things you want to move away from, like a draining friendship or overpriced daily lattes. The second is a list of things to move toward, like reading more or spending time outdoors. It’s the kind of list we often make in January and forget by February. Kirsch suggests a more frequent habit. “What if these new-year traditions became new-month traditions?” she says.

Each month, make your toward and away lists. Name what you want more of and what you want less of. At the end of the month, take 10 minutes to review.

There is support for this practice in the work of many behavior-change experts, like Tony Robbins. Robbins says we’re usually driven by one of two things: what we want to experience or what we want to avoid. When we don’t pause to notice which desire is at the wheel, we end up feeling reactive instead of intentional. This applies to our daily behavior and relationships but also to our spending and saving habits.

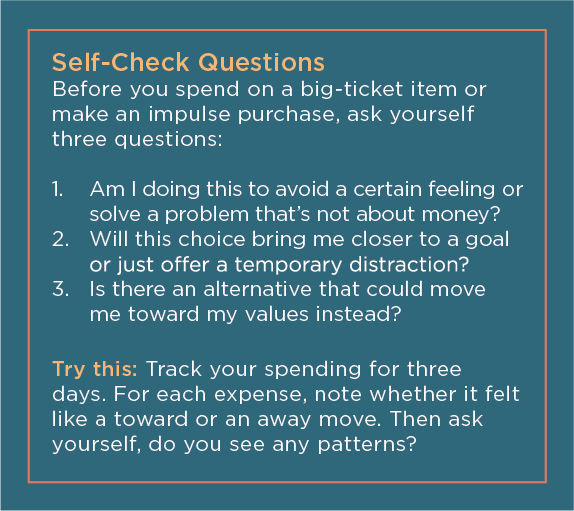

Soon after learning about this list-making method, I decided that, each month, I’d look through every purchase I’d made and ask myself a simple question: was this individual purchase moving my partner and I toward our values and goals, or was it an away move—reactive, impulsive, or driven by stress?

Some expenses were necessary and neutral, like gas and groceries. Others clearly supported our long-term financial goals, like buying in bulk or enrolling in a cooking class to reduce how often we eat out.

And then there were the ones that were clearly reactive: purchases made to soothe, compensate, or avoid. Takeout after a long day because we were too drained to cook. Expensive gifts for our grown-and-flown kids because we missed them and wanted them to feel loved. And those restaurant dinners we had sworn off but still craved when emotions ran high. These kinds of choices aren’t a problem now and then, but we know we need to keep them in check, and we want to be fully aware of what is driving them.

What that list revealed was powerful. It wasn’t about cutting back or blaming ourselves. It was about starting to understand the reasons behind our spending. Were we acting proactively or reactively? Were we leaning into our values or trying to escape discomfort?

Repeated monthly, this practice became a valuable compass. It helped us prioritize saving and align our spending with what we really value, like time with friends and family, time spent outside, and good food.

The next time we met with our advisor, our balance sheet spoke for itself. We weren’t all the way back to where we wanted to be, but we were on track for smarter spending and saving.

A Gentle, Objective Approach

B.J. Fogg, in his book Tiny Habits: The Small Changes That Change Everything, cautions that this type of self-evaluation should be made gently, with positivity. He urges readers not to judge themselves harshly for their own reactive behaviors.

“We change best by feeling good, not by feeling bad,” says Fogg. “Make sure your attempts at demotivating behavior don’t morph into guilt trips.”

Karas agrees. She says most budgeting tools focus on the bottom line rather than the emotional component of spending behaviors and trends. “I’d love to see budgeting prompts like, which purchase this week energized you? or which made you sigh with regret?” Tagging your expenses with the emotions that surround them can turn raw data into reflective insight. Imagine seeing a pie chart not just of dollars spent but of energy gained. That’s the future of fintech with heart.”

If you start to view spending through this lens, you can build more than savings. You can build confidence, alignment, and a greater sense of agency in your life.

By combining intuitive self-assessment with actionable insights, you may also find it easier to make financial decisions and proactive adjustments that align your everyday choices with your long-term retirement and savings goals.

The Takeaway

No one gets this right 100 percent of the time. But noticing the reasons behind your spending is a step toward more empowered choices. It’s not about guilt. It’s about direction.

By taking stock of what’s working and what’s not, you gain clarity on the forces shaping your financial well-being. This framework isn’t a replacement for comprehensive financial planning, but it can offer valuable insights alongside it. While detailed budgets and investment strategies address the mechanics of money management, the toward-and-away lens addresses something deeper: the emotional and psychological patterns that drive your choices.

The beauty of these lists is in their accessibility. While tools like spreadsheets and apps can help, toward-and-away lists start with honest reflection. Over time, self-awareness becomes a quiet but powerful form of self-knowledge, one that can help you make choices that feel both financially sound and personally authentic.

Written by Cara J. Stevens

Have questions? Need help? Call the CAPTRUST Advice Desk at 800.967.9948, or schedule an appointment with a retirement counselor today.